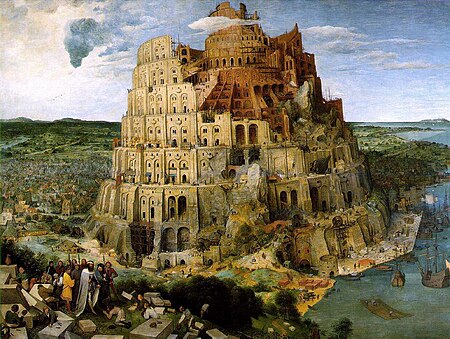

Alas, Babel

This time of mass extinctions spares nearly nothing, from individual taxa to landscapes to human institutions. Within the realm of human culture, nothing is as precious and as precariously preserved as linguistic diversity. The key to its preservation, perhaps counterintuitively, may lie in treating linguistic difference as an ordinary form of expression of rather than a cultural peculiarity.

The latest paper version of Ethnologue tallies nearly 7,000 extant human languages. This number seems destined to decline, perhaps precipitously. As Oz Shy observed in The Economics of Network Industries, a shared language is a network good. The imperatives of globalization and modern communication drive native speakers of diverse tongues toward a single standard. That standard happens to be English. Here at the annual European meeting of the International Telecommunications Society, which I'm attending this week, the working language is English, even though the Universiteit van Amsterdam is hosting and the single largest linguistic grouping among attendees is probably German. The allure of English is strictly pragmatic. Choosing a common language for academic discourse isn't quite as essential as harmonizing the international air traffic control system, but efficiency strongly favors the tongue of the World ... Wide ... Web. The Internet scarcely bears all the blame. If anything, by allowing speakers to target and find microscopic audiences, the World Wide Web may be the last redoubt for unusual languages. Purely passive television is the real cultural nerve gas. Even the word television is a linguistic wrecking ball. With the striking exception of Iceland and the Faeroe Islands -- where sjónvarp, a beautiful neologism combining the Germanic roots for sight and throw, cf. warp (Eng.) and werfen (Ger.), designates television -- the entire OECD uses some derivative of the word television. Even in non-Indo-European countries such as Turkey and Japan, テレビ (terebi) lizards threaten to make a dinosaur of human linguistic diversity. What Nimrod would have the world be of one speech and one tongue?

The Internet scarcely bears all the blame. If anything, by allowing speakers to target and find microscopic audiences, the World Wide Web may be the last redoubt for unusual languages. Purely passive television is the real cultural nerve gas. Even the word television is a linguistic wrecking ball. With the striking exception of Iceland and the Faeroe Islands -- where sjónvarp, a beautiful neologism combining the Germanic roots for sight and throw, cf. warp (Eng.) and werfen (Ger.), designates television -- the entire OECD uses some derivative of the word television. Even in non-Indo-European countries such as Turkey and Japan, テレビ (terebi) lizards threaten to make a dinosaur of human linguistic diversity. What Nimrod would have the world be of one speech and one tongue?The bottom line is the same, whether one is devoted to documenting, in the descriptive tradition of linguistics, the beautiful but threatened diversity of human language, or whether one more aggressively advocates the cause of language perservation. Linguistic diversity seems doomed in an age of globalization, network efficiencies, and sheer speed.

Well, so what if the world becomes, in the grim vision of Brave New World, a linguistic monoculture where German and Polish are vaguely recalled as extinct languages? Given how much of humanity's singularly powerful command over pattern recognition is committed to spoken language, a loss of linguistic diversity has devastating consequences whose magnitude may defy accurate calculation. As documented in works such as John McWhorter's Power of Babel and Mark Baker's Atoms of Language -- see generally Paul Bloom's review of both books -- the phonetic, morphological, and syntactic logic embedded in each language opens a window on the limits and potential of human thought.

In one small but significant corner of this epic struggle against the Goliath of linguistic extinction stands the University of Minnesota's aptly named David Treuer. The subject of a recent profile in the New York Times by Dinitia Smith, Professor Treuer is the author of the newly released book, Native American Fiction: A User's Manual.

In one small but significant corner of this epic struggle against the Goliath of linguistic extinction stands the University of Minnesota's aptly named David Treuer. The subject of a recent profile in the New York Times by Dinitia Smith, Professor Treuer is the author of the newly released book, Native American Fiction: A User's Manual.What exactly does David Treuer's new critique of Native American fiction -- especially the popular and highly regarded works of writers such as Louise Erdrich, Leslie Marmon Silko, James Welch, and Sherman Alexie -- have to do with linguistic preservation? Everything. In the words of Dinitia Smith, David Treuer "argues that the works of Indian authors are often read as ethnographies, when they should be read as literature."

Professor Treuer has backed his literary criticism with his own actions. For the next year and a half, he will record, transcribe, and translate the Ojibwe language. This effort to preserve Ojibwe dovetails beautifully with his "criticism of exceptionalism in Native American literature." When the literature of a culture threatened with linguistic annihilation is seen as culture itself and not as some sort of anthropological artifact, perhaps then we might glimpse the path toward preserving the human diversity that makes such culture -- in all of its beautiful diversity -- possible in the first place.

3 Comments:

I like this point particularly:

"Given how much of humanity's singularly powerful command over pattern recognition is committed to spoken language, a loss of linguistic diversity has devastating consequences whose magnitude may defy accurate calculation."

But I think your unease here may be grounded more in aesthetics than, say, ethics or efficiency. I'm reminded of Tim Wu's review of Chris Anderson's The Long Tail. Anderson argues that all the diverse content in the "long tail" is extremely valuable. Wu agrees, but points to a counter-value: standardization.

We can see many entities growing stronger as they gain a common language; see, e.g., Eugen Weber on the standardization of French language (which was imposed on regions with dozens of dialects), or more recently Larry Siedentop's observation that there can likely be no common European public sphere without a common language (which he, an Englishman by way of the US midwest, naturally suggests should be English).

Perhaps the ideal would be for many large blocs of "second languages," which would enable various smaller "first languages" to flourish within them.

In positive news, Microsoft is evidently providing support for the Quecha language. Hat tip to Daniel Sokol for bringing this item to my attention.

Quick follow up: Here is a link connecting interested readers to Daniel Sokol.

Post a Comment

<< Home